Mersing, Malaysia

After 5 days at sea, at last, we saw land the morning of December 20,1980. It was an island of Malaysia called Tioman. That evening, we arrived to the island of Pulau Tengah, off the eastern shore of the Malay Peninsula. We were not allowed on the island, which was the site of a small refugee camp with about 200 people from Vietnam. We were instead directed to Mersing, a small Malaysian town across the strait between Pulau Tengah and the coastline.

It was late in the evening of December 20th, and from the dark sea where we were, we saw city lights beckoning from afar. Common green and red traffic lights appeared to us like twinkling stars from the Promised Land. But as we came closer to the shore, waves became taller and taller, stronger and stronger, probably due to shallower waters and stronger tides. Our boat was terribly shaken, and for the first time during that trip, I had the feeling that all of us were going to die right at the moment when we reached our port of destination. I started to feel the irony of the situation.

All lifesavers had been taken. My oldest son could find only a wooden plank that he held on to. I did not have anything to cling to. In my arms, I was squeezing my other two boys. If the boat sank, we would be going down together. I did not know what my wife was doing at that moment; she never came out of that fish storage space since we left Vietnam. After a while, the crew succeeded in stabilizing the boat. We decided to wait until morning to try to approach Mersing again. We successfully reached the pier without incident. Members of the Malaysian Red Crescent Society (the Red Cross equivalent in Islamic countries) came forward to receive us. They were very happy to find out that there were two doctors among the refugees, and both of us and our families were processed quickly on arrival, without the customary body searches. Dr. L. P. Q. and I were classmates at the Saigon Medical School. We also used to work together at the military Cam Ranh Rehabilitation Center, before we moved to Saigon upon the arrival of the communists.

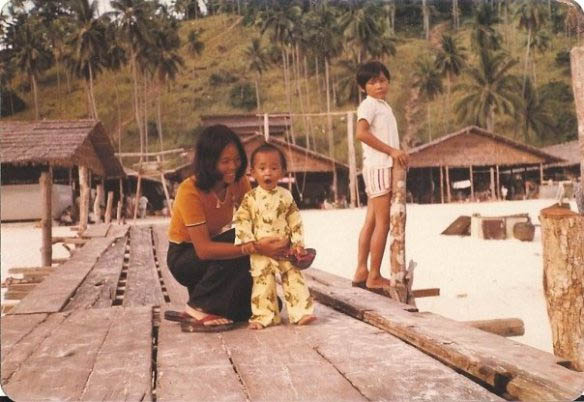

In Mersing, we lived in makeshift tents in a park by the sea. My children got their first bath at a stream nearby. They played and fought happily on the sandy bank when the youngest one suddenly fell with a splash into the water. Fortunately, I reacted quickly enough and saved him. Someone had threatened to throw him into the sea at the beginning of the trip, which really scared his mother as it could have been a very bad omen.

After three days, we were moved by boat to the island of Pulau Tengah, about an hour from Mersing.

My two months in Pulau Tengah.

On Christmas Eve 1980, all of us, about 130 people, were transferred from Mersing on the East coast of Malaysia (population about 20,000) to the island of Pulau Tengah, 16 miles away, now an uninhabited Marine Park where tourists can watch leatherback turtles coming ashore to lay their eggs. It was a short trip by boat. The island was about one mile long North-South and much narrower East- West.

“At only a mile wide and several miles off the coast of Malaysia, the island has been inhabited by only three known groups of people. Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s and 1980s, the crew and cast of Expedition Robinson (Swedish version of Survivor) from 1998-2010, and currently, the staff and guests of the Batu Batu resort. (“http://jason-ludt.blogspot.com/2013_09_01_archive.html”)

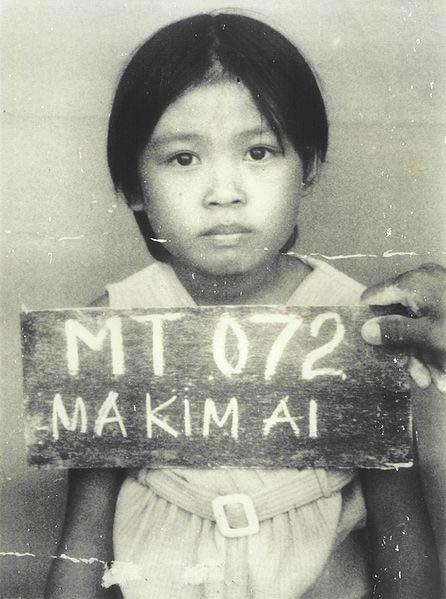

There were two refugee camps, North Island (Bắc Đảo) and South Island (Nam Đảo). The reception buildings were in the center of the island, facing the pier, across the dirt road that joined the two camps together. All new arrivals were registered, photographed. Each of us had an ID picture taken, with the number of our boat (MH 3273) and our name written in white chalk on a small black board on our chest. We were issued ID cards from the International Commission for Migration (ICM).

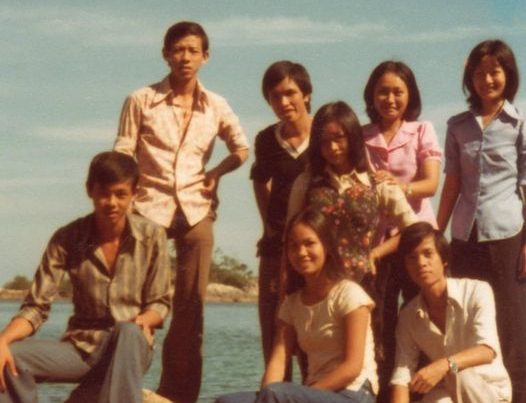

The staff interviewed us in Vietnamese. Refugee volunteers were organized into a committee that worked quite effectively in cooperation with Malaysian authorities and charity organizations. Even between people from the same country, there was a lot of language barriers among some refugees who spoke different Vietnamese minority dialects, in particular Chinese Vietnamese and people coming from small, isolated islands along the central Vietnamese coastline. Each refugee had to declare his or her past history, the members of his nuclear and extended family still in Vietnam and their current locations or activities. Malaysia was a country on the “free world’ side and certainly needed to screen out unwanted elements that communist Vietnam might want to insert into the boatpeople community. After all that paperwork, we now become “illegal residents under detention” in Malaysia, waiting for resettlement in a “third country”, hopefully the United States. It was Christmas time and Catholics were getting ready for a special mass at the community hall that night. The priest was French and because, like most Vietnamese doctors, I was fluent in French, someone asked me to serve as an interpreter for him during the mass. It was an honor, though I was really exhausted and needed time to find some place for the children to spend the night. Also, my knowledge of French terms used in a mass was rudimentary at best. I had never attended a mass in full length, in Vietnamese or in French. So I felt relieved when some one took over the job. Then, my surgeon friend and I were immediately offered the honor of running the small hospital of the island, the only structure with air conditioning and that looked like a real building. We would operate an outpatient clinic, admit to our small ward the more severe cases and send the worst cases to a hospital in Mersing or Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. We would also review the chest X rays of all refugees, taken by a fellow refugee cursorily trained as a radiology technician. We would clear the normal X rays, and send out the suspicious ones to radiologists in Kuala Lumpur for a more thorough interpretation.

We were led to the North Island camp where we found a few wooden cot beds in makeshift huts with thatch roofs. Some from our boat also stayed there for the night. We had some food, settled down a little with our few possessions, and put the children to bed. Then, my wife and I went to the church at the center of the island to attend midnight mass. As we walked down the small dirt path along the seashore, waves almost came to our feet and moisture from afar, perhaps from our native land, came to wet our face and awoke us to reality. At the mass, the choir was singing, accompanied by a guitar. Tears came to my eyes and I could not help sobbing forcefully. It was the end of our life as we had ever known it. This was the painful birth labor of a new life in a new language, a new society, and a very uncertain future.

After a while we moved in to a communal building. It was a large and hollow hall built with light material and a roof made of palm leaves. Large cots made of wood planks were used as living and sleeping quarters for a dozen families. Ours of five was allowed about the space a king-sized bed. It was next to Dr. Q. and his family. I remember this detail because I still can visualize him sitting on his mat reading medical textbooks available from the hospital. Both of us tried to catch up in our English and our medical knowledge. We knew that we had a lot to learn, as we wanted to go back to our medical career eventually after our resettlement in a third country.

Good as well as bad things happened here. It was an idyllic place, with perfect beaches, coconut palm trees and a blue sea that would fit perfectly in any Caribbean Sea travel catalogue, except for a few oddities that would remind a visitor that this was not a paradise island. There was no latrines but large outhouses built over the ocean where human wastes were recycled by the sea’s fauna. Our clothing was colorful and diverse; donated items from different places of the world reflected a variety of fashions and tastes. From jeans to blue Filipino traditional shirts, we valued everything we got and happily wore them. There were times when they sorted out big bags containing everything from pants to underwear, and the best-connected people had the privilege to pick up the most sought after items. My second son was missing his aunt T. very much because she had been taking care of him over the years and was very close to him when we were still in Vietnam. Once, looking at all those jeans, he told us: “Let’s keep some of those blue jeans for Di T.”. That remark from our 6-year-old kid reminded us how despondent we had become.

My children had no school to go to except some youth activities at the camp’s library at the seaside. There, for a few hours a day, some refugee volunteered to play or to read with the kids. My 5-year-old youngest boy was very reluctant to go there. He resigned to stay with the other children only after Mr. Hữu, one of our escape boat’s owners who used to pamper him a lot, bribed him with a little bowl of hủ tiếu (Southern Vietnam’s rice noodle soup). It was a very precious fare at the time, bought from one of the makeshift cafés operated by refugees, and then I had to promise to stay within his sight all the time.

The brightest moment for me was when I was able to contact the American Medical Association (AMA) in Illinois. I could not bring any official document with me during our escape , and my name and ECFMG (Educational Council For Foreign Graduates) ID number (that I had taken care to memorize when we left) were my only proof of identity. I wrote a letter to the ECFMG office in Illinois that Ms Chen, a Chinese nurse, volunteered to mail from the Mersing (inland) post office. Only a few weeks later, to my greatest surprise, I received a very nice letter from the AMA welcoming me to the Free World and explaining that it still had all my documents submitted to them ten years before when I applied for the exam in 1971, and that they were sending the originals back to me after having made a copy of everything.

I had passed the ECFMG exam in 1972. In fact, when I took the exam, I never thought of any possibility of ever getting my training in the US. I just did it from curiosity and for fun, as a few of my friends did at that time. A few of us just tried to see how we, as from a “local, third world’ medical school, would fare on an international exam. We didn’t even have to pay exam fees beforehand; if we passed, they were waived until the day we actually reached the US and actually made use of the certificate. Now, I felt really grateful to the right company of friends who made me do something of no apparent importance then, but that turned out to be of monumental consequence to my family and myself ten years later.

The ECFMG gave us back our identity, and even earned me some respect from the Filipino nurses who were also looking for an opportunity to work in the US. Later, in America, the fact that I was already qualified for an intern position spared me years of intensive preparation without a salary.

As said before, bad things happened too. Within the first few days after our arrival, people from the North Island camp were rushing toward the hospital, carrying a livid and flaccid boy of one or two years of age. He had somehow fallen into one of the wells there. Somebody inadvertently had left the cover open or maybe the kid had somehow managed to open it by himself. “Ghosts led his way, the devil showed it to him”, as we like to say in Vietnamese. (Ma dẫn lối, quỷ đưa đường). I tried to resuscitate him, mouth to mouth and everything, to no avail. His family owned the boat that brought us to the island. A few among us thought of the accident as a sinister fee of passage. Soon later, a very athletic and well-built man, from the same family, suddenly developed abdominal cramps and became comatose. He had drunk some mixture of coconut milk and a certain solvent found in an abandoned can. It was a very toxic compound. After a few days at our hospital, he died soon afterward of very painful death. There was very little Dr. L. P. Q. and I could do for him at the little hospital. In fact, coming from a country where medical care had regressed to the most rudimentary level under years of communist regime and American embargo, our expectations had gone so low. We did not even have any idea of what could be done elsewhere (in Kuala Lumpur for example) for such a case, and how to proceed to refer and transfer our patient to some other place where he could have a better chance for survival. This tragic case heightened our awareness about poisoning and alcohol abuse that were very prevalent among the refugees. Another memorable case involved a teen-ager who tried to do some fishing to improve his family meals. The hook in its flight accidentally perforated his eye globe, he never reported to the hospital and when we found out about the accident it was too late. Idleness coupled with extremely crowded living conditions created an environment favorable to many sins that would not have thrived otherwise, like drunkenness, gambling, violence and recklessness. Almost nobody cared much about anything besides their own survival. Occasionally, right before our eyes, whole boatfuls of people who were refused permission to land by local authorities were chased away and disappeared into the horizon.

Looking for an adoptive country

In Pulau Tengah, we had the first chance to contact with delegations from the third countries. We were refugees from Vietnam, therefore Vietnam was our first country. The second country was Malaysia, where we were illegal immigrants, and tolerated temporarily until another one voluntarily accepted us for political asylum. That last country where we would eventually go to live was called the third country. Because of past political and military ties with South Vietnam, the United States had been the most willing to accept us. In fact, in the previous years, most Vietnamese who made it to refugee camps had been readily accepted for resettlement in the United States. Exceptions were people who were rescued at sea by another country’s ships. By international convention, they were automatically accepted for resettlement in that respective country, like Germany, Sweden, even Israel.

By 1981, so many Vietnamese had settled in the United States that there were signs of “fatigue” in their open arms policy. Also there was economic hardship in the US, something that I was not aware of then.The Americans changed their immigration policy and did not automatically accept even former military officers of South Vietnam who had fought on their side during the war. My credentials, like having a professional degree recognized in America (my ECFMG certificate would allow me to find a paying position in a hospital in the US) and having spent time in a communist concentration, did not help either. The Americans required us to apply to two other countries and to be rejected by them before they even open a file for us and consider our application. Therefore, I had to apply with the Australian delegation first. Australia wanted only very young, single applicants at the time; I guessed that they wanted mostly young, cheap labor force that didn’t have the burden of a large family. Many uneducated, non-English speaking men in their twenties were accepted to Australia without significant delay. We felt a lot of bitterness then, but in retrospect and in a philosophical sense, I think that it was probably fair. Sometimes, someone else needs his own dose of good luck, and we cannot expect to keep our own socioeconomic advantage all the times.

We had the same misfortune with the Canadian delegation. I still remember the Asian Canadian who courteously told me that doctors were not encouraged to come to his country. Again, it became a pattern here. We were being rejected because we were overqualified for their use. Laughing at this Catch 22 situation was probably a good coping strategy for us. Later, I thought of it as another example of the Law of the Frontier Man who lost his horse. The story of the frontier man (tái ông thất mã) is a cliché in Chinese popular philosophy. That man lived at the Northern border of China, near the Great Wall. He lost his favorite horse and his friends felt sorry for him. He said: “I am not sure it is not a good thing”. One month later the horse returned home, bringing along another tall and white horse. His friends congratulated him for his luck. He said: “I am not sure it is not a bad thing”. His son rode the new horse, and broke his leg. Bad luck? Maybe not. There came the war, everybody fit person was drafted to the military. Nine out of ten people died in the war, the son survived. You have understood the pattern now. So, later, when I became well established and comfortable in the warm weather of Virginia, looking across the Canadian borders at my friends who fought the freezing climate for most of the year, “tái ông thất mã” came back to my mind. But, I know, as part of the rule still, who knows what may happen next?

Epilogue:

The Pulau Tengah Camp closed its door in the spring of 1981. We spent several months in the transit camp of Sungei Besi, near Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia, before we were accepted for resettlement in the US. However, due to a new policy in Washington, our departure was delayed furthermore. After 6 months of required English language training and “cultural orientation” (teaching us about the American lifestyle) in in a Refugee Processing Center in Bataan, in the Philippines, we finally boarded our flight to Newport News, Virginia, via San Francisco.

[This article, edited and illustrated for the Web, previously appeared in the book “The Vietnamese Mayflowers of 1975”, published by CreateSpace, in 2009 (Editors: Chat V. Dang, Hien V. Ho, Nghia M. Vo, An T. Than and Ann R. Capdeville), and The Vietnamese Boat People,1954 and 1975-1992 (Editor: Nghia M. Vo.]

J. B. Ho

12-12-2008

12-30-2013

Photo credits:

1) Vagabundo de la tierra

2) Remembering the Vietnamese exodus

href=”http://www.refugeecamps.net/index.html” target=”http://www.refugeecamps.net/index.html>

3)href=”http://batubaturesort.wordpress.com/category/un-refugee-camp-1975-1981/” target=”http://batubaturesort.wordpress.com/category/un-refugee-camp-1975-1981/

4) Archive of Vietnamese boat people (< href=”http://vnbp.org/” target=”_blank”>vnbp.org</>)

5) Wikimedia Commons