By Frank Snepp

The small weathered flag of the Republic of Vietnam, which I bequeathed to the Vietnam Heritage Museum in Orange County, October 20, 2019, is a sacred relic of the tragedy I witnessed first-hand in Vietnam and a chastening reminder of the moral debt I will always owe to my Vietnamese friends and allies.

The flag was with me throughout my six years as a CIA officer assigned to support the nationalist cause. It was silent witness to almost every major event I experienced in Vietnam during the critical period, 1969-1975, including the final evacuation itself. It is a memorial to lives lost, dreams betrayed, and victories that might have been.

Soon after my arrival in Saigon in the summer of 1969 I bought the flag from a street vendor. For the next two years it remained on display in my small apartment on Nguyen Hue Boulevard, where it survived several shelling attacks, and finally on the wall of my CIA office on the sixth (top) floor of the embassy.

Soon after my arrival in Saigon in the summer of 1969 I bought the flag from a street vendor. For the next two years it remained on display in my small apartment on Nguyen Hue Boulevard, where it survived several shelling attacks, and finally on the wall of my CIA office on the sixth (top) floor of the embassy.

It remained forever in my thoughts, a constant evocation of the Vietnamese lives at stake in my work, as I traveled around the country interrogating prisoners, defectors and intelligence sources, writing strategic assessments for the Ambassador, and reporting on the progress of pacification and Vietnamization.

It was first thing you saw when you entered my inner sanctum at the embassy, a branch of the CIA station, created in 1964,which drew on all-source intelligence to evaluate every aspect of the war, from the situation in Laos and Cambodia to the viability of the South Vietnamese government and military to the status of Communist forces and intentions.

In mid-1971 I carried the flag back with me to CIA headquarters and kept it inside my desk at Langley as I spent the next year analyzing North Vietnamese policies for the CIA’s Vietnam Task Force. When I returned to Saigon in late summer 1972 to interrogate a high-ranking prisoner, the flag accompanied me and I frequently carried it with me to the National Interrogation Center to remind prisoners there of a cause greater than theirs, a cause sanctified by the blood of Vietnamese patriots and rooted in the ancestral lands of all Vietnamese.

On January 27, 1973, the day ceasefire went into effect, I draped the flag across my desk at the embassy and toasted it with a celebratory cocktail in hopes that those whose lives and dreams it exemplified might come to know peace and freedom.

In the summer of 1973, when a major defector from the Communist Command crossed the lines and offered to work with us, I brought the flag with me to one of our first meetings and tried to help him understand what it stood for, a nationalist cause that had nothing to do with the colonial exploitation the Communists tried to attach to it.

As the war heated up again, the battle maps hanging alongside the flag in my office began to show the slow advance of Communist forces and the buildup of a new infiltration corridor along the Laotian border known as the “Third Vietnam.”

On my desk beneath the flag, reports began piling up from a patriot spy, a Vietnamese agent buried inside the Communist command who’d been working for the nationalist cause since the mid-1960’s and who had given us advance warning of many strategic decisions by Hanoi. I came to believe the spiritual force embodied in the flag was the same force that motivated this agent, whose name was Vo Van Ba. I hoped this same force would keep Vo Van Ba safe to continue performing his heroic work for the free peoples of South Vietnam.

After Communist forces overran the northern half of the Republic in March 1975, I received the latest report from Vo Van Ba, a warning that the Communists meant to isolate and seize Saigon in the next few weeks and that they viewed all talk of a negotiated settlement simply as a diversion to keep the Americans and South Vietnamese off balance.

Alongside the flag in my office I hung a list of loyal Vietnamese who would need to be evacuated in the event of an emergency. It quickly grew in size, with the numbers of Vietnamese deserving our help growing into the millions.

The battle maps alongside the flag began bleeding red as I marked in red ink the advance of Communist forces on Saigon.

But the U.S. Ambassador, Graham Martin, refused to believe Vo Van Ba’s warnings. He was persuaded by French diplomats and other foreign observers, who were close to Hanoi, that a negotiated settlement was possible, making an emergency evacuation unnecessary, if only Nguyen Van Thieu stepped down in favor of a neutralist, General Duong Van “Big” Minh. Henry Kissinger received similar false assurances from the Soviets.

On April 17, as the last government defenses at Xuan Loc were collapsing, I placed my hand on the flag, gave up a silent prayer and then set off to meet directly with agent Vo Van Ba. I had talked with him periodically over the years, written hundreds of “requirements” (intelligence questions) for him and come to view him as the most important intelligence source we had ever had in Vietnam, working against the enemy. I now wanted to verify the Communists’ latest intentions and thus to try to nudge the Ambassador into accelerated evacuation planning.

At great peril, Vo Van Ba met with me, told me the Communists meant to launch their final drive against Saigon with air and artillery strikes in time to beat the monsoons to Saigon in early May – just two weeks away. He reiterated that there was no chance for negotiated settlement.

In a later declassified CIA history of the war, Thomas Ahern cites Vo Van Ba’s statements to me. By Ahern’s account the agent told me “it no longer mattered what Saigon did. He reported a Communist intention to ‘fight on until total victory, regardless of whether the Nguyen Van Thieu government falls or the U.S. decides to give aid to Vietnam. There will be no negotiations and no tripartite government.’ The report went on to assert that the North would rather sacrifice troops in a final drive than ‘waste time trying to achieve victory through a coalition government… The Communists now plan to celebrate (Ho Chi Minh’s birthday) in Saigon’.”

I returned to my office and beneath the flag hastily distilled Vo Van Ba’s warnings into an intelligence report(the one excerpted above). But Martin and my own immediate boss, the CIA Station chief, again dismissed these warnings, and would only allow me to send the report out through a low-priority “operational channel.”

Nonetheless, when it reached Washington its importance was immediately recognized. It was highlighted in the President’s Daily Brief on April 21, and helped persuade Admiral Noel Gayler, the U.S. commander in chief in the Pacific, to order that the embassy grounds in Saigon be outfitted to receive large helicopters from the fleet in case an emergency evacuation became necessary.

On April 25, beneath the small flag in my office, I was told that I would secretly chauffeur Nguyen Van Thieu to Tan Son Nhut that very evening so that he could catch a black flight out of the country, the hope being that this would pave the way for a negotiated settlement.

It didn’t. Indeed, resistance to evacuation planning mounted within the embassy as the U.S. Defense Attaché and his staff joined Ambassador Martin in predicting that the Communists would settle for a negotiated ending to the war, contrary to Vo Van Ba’s warnings.

Some embassy officers tried to bypass the Ambassador and mount a makeshift “Vietnamese” airlift, using newly emptied cargo planes and aircraft dedicated to the removal of the American staff of the Defense Attaché’s Office. But lack of inter-agency coordination, self-interest on the part of the DAO’s own personnel, and the Ambassador’s refusal to permit early departure of high-ranking South Vietnamese military officers or government officials reduced this informal “air bridge” to a case of “every man for himself.” High risk Vietnamese were left standing on the tarmac while bar girls and friends of DAO officers got first priority in the boarding lines.

Meanwhile, conflicting agendas within the embassy and poor intelligence work by DAO staffers prevented the mounting of an overland exodus to Vung Tau that might have enabled thousands of imperiled Vietnamese to be evacuated off the beaches before vital land routes were shut down by the Communists. The main highway to the coast was severed on April 27.

The following day, just moments after “Big” Minh assumed the presidency, stolen government aircraft flown by North Vietnamese pilots and defectors blasted the runways at Tan Son Nhut. Overnight, Communist rockets and artillery opened upon the airfield and the peripheries of the city, and every report and rumor of a negotiated settlement proved false, just as Vo Van Ba had predicted.

The following morning, Ambassador Martin personally inspected the obliterated runways at Tan Son Nhut and recognized the obvious: they would never be able to sustain a major fixed-wing airlift.

He finally consented to an emergency helicopter airlift for Americans and 9,000 Vietnamese, but he remained hesitant to shut down the embassy altogether for fear of heaping ignominy on humiliation for the U.S. I was told I would be part of a 50-man CIA stay behind contingent.

At that point I bundled up the flag and hid it away in my CIA briefcase. But a short while later, I noticed an intercepted enemy radio message that pointed to a massive artillery attack on central Saigon unless all Americans were out of the country by 6p.m. I warned the Ambassador.

Apparently, Henry Kissinger saw the same intelligence in Washington for just before noon, Saigon time, the Ambassador was advised by the White House that all Americans would be leaving on the helicopters soon to arrive from the U.S. fleet offshore.

Those of us who made up the final working staff at the embassy and at DAO spent the rest of the day trying to locate Vietnamese employees of various American agencies and move them to the embassy grounds or a section of Tan Son Nhut designated for helicopters shuttling to and from the fleet.

At around 9:30 p.m., the last 17 CIA staff officers still inside the embassy compound, myself included, were ordered to leave via helicopter from the rooftop pad. Inside my briefcase I carried the small Vietnamese flag that had been my spiritual companion for so many years.

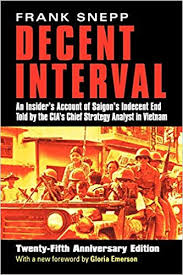

After resigning from the CIA in early 1976, I began writing a memoir about the fall of Saigon, Decent Interval, that was designed to shame the U.S. government into mounting diplomatic or covert initiatives to try to rescue loyal Vietnamese we had left behind.

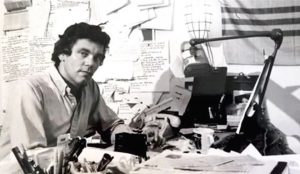

Hanging over my writing desk was my old flag from Saigon. I kept it within easy view in memory of those Vietnamese and Americans who had given so much in the name of the country and the ideals which the flag represented. I also came to see it as a tribute to the agent, Vo Van Ba, who had made the ultimate sacrifice for the nationalist cause.

In my book Decent Interval, I revealed what he had done, but did not attach a name to him because the operation of which he was part was still classified. Only years later did I learn that he had been betrayed by an American captive and Vietnamese leakers, that he had been captured by the North Vietnamese within two days of the fall of Saigon and had reportedly committed suicide soon afterwards.

In my book Decent Interval, I revealed what he had done, but did not attach a name to him because the operation of which he was part was still classified. Only years later did I learn that he had been betrayed by an American captive and Vietnamese leakers, that he had been captured by the North Vietnamese within two days of the fall of Saigon and had reportedly committed suicide soon afterwards.

For me, part of the blood-red striping of the old flag represents the martyrdom of this unsung Vietnamese hero.