Galang rests quietly in the calm sea, indistinguishable from the thousands of other green Indonesian islands near Singapore. But for tens of thousands of Vietnamese “boat people,” the United Nations refugee camp here has represented a single, thin ray of hope. For most of those who board small, rickety boats to escape Vietnam in search of new and happier lives, Galang will not prove to be what they hoped to find.

Laying a thick trail of oily diesel smoke low across the glassy sea, our noisy boat seems a gross violation of nature’s tranquility as it slices toward the wooden dock on this tiny, emerald isle. One would never suspect this forested point of land protruding unassumingly from the warm ocean to be home to nearly 20,000 desperate people who have no idea what their future will hold. They have risked everything in the belief that their new lives, or the lives they hope to live someday in another country, will prove better than those they left behind.

The people who have made it here already passed a very difficult test. They rolled the dice on a dangerous ocean voyage and won. Many others lost that gamble. Pirates troll the seas in search of easy prey, and often find it. Many Vietnamese are robbed, killed or raped shortly after they gather their meager possessions and set off in the cloak of darkness in search of freedom and opportunity. A small shrine in the camp pays tribute to three women who, after suffering the humiliation of rape during their journey, took their own lives.

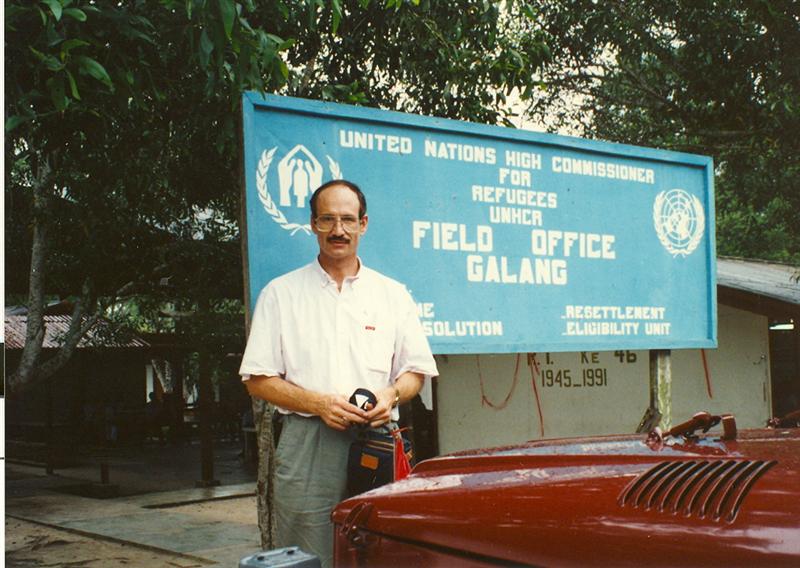

My seven Congressional staff colleagues and I are greeted warmly by camp staff and U.N. workers whose difficult job, beyond providing meager shelter, rations and minimal health care, is to determine which of those people arriving will qualify for refugee status and possible resettlement in other countries. For those who are unable to prove themselves political refugees under United Nations definition, or who have no close relatives in other countries to sponsor them, the future is bleak: They can either return to Vietnam or remain in the camp, hoping against hope to someday be “saved.” Most do not qualify for resettlement. Still, few of those rejected will voluntarily return to the conditions that forced their exile.

At a briefing, the camp commander reveals that Galang was established at the end of the Vietnam war and built to house only a quarter of the population now living there. Over the years, the United States has accepted 82,060 of those who survived their ordeal and qualified for resettlement. Canada became home to 13,516 people, followed by Australia’s acceptance of 6,470. Other countries have not stretched their arms as widely. Japan accepted only 113 people. Spain, Italy, Argentina and Ireland took fewer than 20 each. Meanwhile, scores of people continue to arrive from the open sea on overloaded vessels. An additional 50 are born here each month.

The pressures on Galang have intensified as other nations have strengthened their resolve not to accept any more “boat people.” Often, the overloaded boats are simply pushed back to sea. Some of them eventually find their way here.

After our briefing, a security truck, red light flashing, leads our caravan of four jeeps on a tour of the camp. Actually, there are two camps. Two camps, and a place unofficially and grimly known as “Camp Three.” It is the cemetery on the side of a hill.

Light rain is falling as we stop to talk with people and take pictures of small, open air roadside shops. Other than money brought with them, or funds sent by relatives, the people here have no financial resources and very limited ability to earn money. But the prospect of minimal sales to each other and to island visitors is enough to maintain a few tiny food stands and small, wooden stores carrying basic supplies.

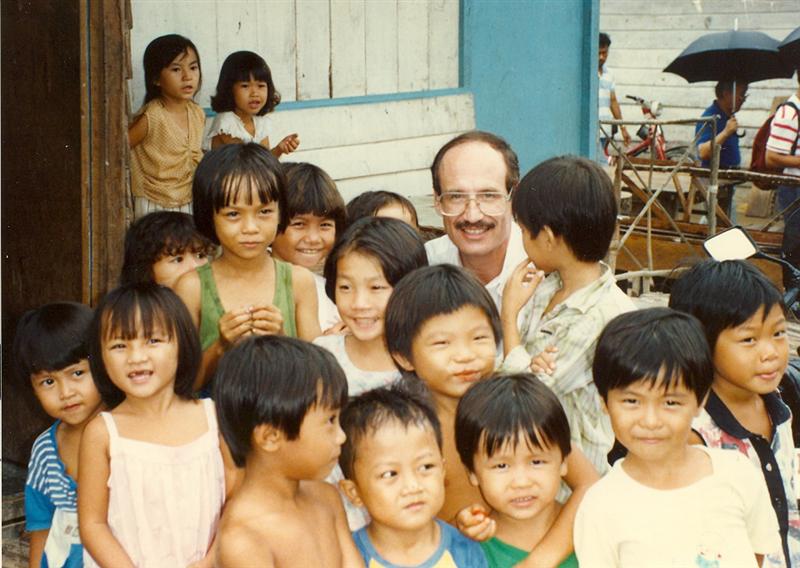

There is the hollow expression of resignation and sadness on some of the older faces, but not the children’s. Excited by the parade of visitors, they eagerly pose for pictures and hesitatingly try out the English phrases they have learned. Giggled calls of, “Good morning, sir,” or “Nice afternoon, sir,” ring out recognizably from the noisy chatter as we shuffle conspicuously along the small road. We return the greetings, to a reaction of giggles and laughter.

Nearby, under a small shelter, the serious business of casting fates is conducted. A U.N. employee, in this case a pleasant and caring attorney from Washington, interviews each person who arrives, and soon determines whether the qualifications for resettlement can be met, whether an individual is to be “screened in” or “screened out.” That decision makes all the difference. With the passage of time since the war, increasing numbers of applicants are found to be economic migrants, not refugees, therefore not qualifying for resettlement in the United States or other countries. The interview sometimes lasts more than an hour, but more often than not, 80 percent of the time, the decision rendered is unfavorable.

As we mill about and through interpreters talk with people whose fates will soon be known, I spot a pretty young girl in a clean white dress standing quietly by herself. She backs away as I approach, but after my urging is interpreted she finally agrees to a photo with me. Her voice is soft and quiet. She doesn’t smile. I ask her age. She is seven. I ask if her parents are also in the camp. She doesn’t answer immediately, but then speaks quietly and unemotionally. The interpreter hesitates, then says, “This little girl doesn’t know where her parents are.” Trying not to speculate on their fate, I look down at the little face and start to ask another question. But my eyes have suddenly become misty, and my words won’t come out.

Walking slowly down the dirt road, I ponder the distant political forces which brought that little girl to this place. I recall a note pinned to flowers at the funeral for victims of the air disaster in Scotland several years earlier. Before that flight departed, a man waiting to board a different plane had met some of the passengers. After the crash he sent the note which said, “To the little girl in the red dress….you didn’t deserve this.” That was certainly true, and it tugged at the hearts of millions worldwide who watched the drama unfold on television. But this little girl in the white dress didn’t deserve her fate either, and nobody even knows about her.

Our little caravan winds its way through the rest of the camp and past the place where a fifteen foot boa constrictor has recently been dragged from a small river by excited young men. A few minutes later we arrive back at the small pier. In a place where every person’s prayer is to someday leave, I feel guilty that we, who already have so much, will be the only passengers on the only boat departing that day.

After formalities and handshakes, the boat’s motor belches to life and we slowly pull away. Standing on the deck, I strain to see the main camp. But it is behind the hills and hidden from view, just as the anguish of the people who live here is hidden from world view. As the island shrinks into the horizon, my wave goes unseen by those on the dock. Finally, as the island disappears entirely, I ponder the lives of the thousands of people who have felt driven to cast their fates to the wind, not knowing whether Galang Island will be their first stop on the road to freedom, or their last.

Now, many months later, I still think about and am haunted by that place, and particularly by my memory of the quiet little dark haired girl in the white dress. Just before we left the processing center that day I had spotted her again, walking down a dirt path. She stopped and looked at me without expression for a long moment. Then a hint of a smile crossed her face and she raised her right hand in hesitant wave.

I could never forget that wet, hilly place at the opposite point on planet earth, and will think often of those people who call it home. Especially, I will think of that quiet and trusting little girl. It will come as a recurring stab of pain that I will never know what happens to her. There is no way for me to find out. I never even knew her name.

There are things in life that must be seen and felt to be truly understood, and once understood have the power to fundamentally and forever change us. For me, Galang, the island of burning hope and bitter despair, is such a place.

About the author

From Don Hardy website: As Chief of Staff to U.S. Senator Alan Simpson – and later as a director and senior policy advisor to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, Don traveled to many regions of the world, meeting with various political leaders and being introduced to many cultures.